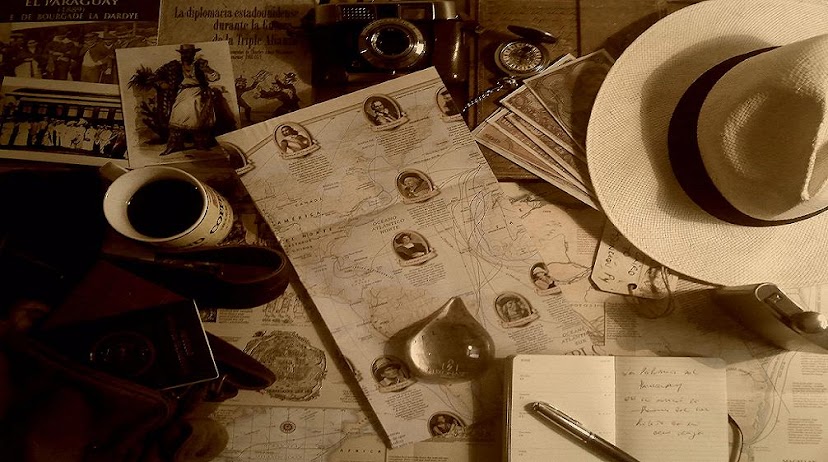

Travel Journal through Paraguay and Argentina

June 2008 by Mali Phonpadith

What was my experience like visiting Paraguay?

One thing that I can say with full honesty is that the people I met and shared time with – made the country more amazing and beautiful than I had imagined it to be.

To summarize my full week exploring the country side…and many sides…of the country, I must first begin with the warmth I felt in every household I was received in. Yes, speaking Spanish helped with the communication flow but even without the language, I would have understood everything they were offering me. I stayed with my friend, Marcela’s family and they absolutely treated me as nothing less than that! They made me laugh, they made me cry, they made me sing, and we even danced around in the living room…laughing so hard we couldn’t breathe…a long story with bananas…at least we were able to capture that on film!

Marcela’s grandmother – a fellow poet – within 30 minutes of meeting me, searched her entire room to find me a gift that I could remember her by. I joked that she should wait to give it to me in six days, they day that I will be leaving her! But she wouldn’t have it- she did not want to forget and she did not want to be forgotten! It was a pen, to write down what my heart wished to explore. This pen had a calendar and she asked me to remember the day we met, the day we shared stories about our past loves and our hopes for a lifetime full of more love.

I tried every traditional Paraguayan dish that exists, except for the bori-bori…perhaps that was meant for my next trip back. On our way to every new town, we looked for a chiperia alongside the roads. Chipa was the perfect winter morning snack…so warm and filled with wonderful cheese and dough that melted in your mouth before you even took one bite. There is no denying that I came back from my South American adventure with a few extra wonderful pounds…making my shape a bit more round than I prefer and yet I could not even justify any guilt or regret for having tried such delicious flavors. The list of traditional foods included mbeju, gnocchi, sopa paraquaya, milenesas, lomitos arabe, chorizos, chipa guazu, barbecue meats of all types “a la parilla” and empanadas.

June 2008 by Mali Phonpadith

What was my experience like visiting Paraguay?

One thing that I can say with full honesty is that the people I met and shared time with – made the country more amazing and beautiful than I had imagined it to be.

To summarize my full week exploring the country side…and many sides…of the country, I must first begin with the warmth I felt in every household I was received in. Yes, speaking Spanish helped with the communication flow but even without the language, I would have understood everything they were offering me. I stayed with my friend, Marcela’s family and they absolutely treated me as nothing less than that! They made me laugh, they made me cry, they made me sing, and we even danced around in the living room…laughing so hard we couldn’t breathe…a long story with bananas…at least we were able to capture that on film!

Marcela’s grandmother – a fellow poet – within 30 minutes of meeting me, searched her entire room to find me a gift that I could remember her by. I joked that she should wait to give it to me in six days, they day that I will be leaving her! But she wouldn’t have it- she did not want to forget and she did not want to be forgotten! It was a pen, to write down what my heart wished to explore. This pen had a calendar and she asked me to remember the day we met, the day we shared stories about our past loves and our hopes for a lifetime full of more love.

I tried every traditional Paraguayan dish that exists, except for the bori-bori…perhaps that was meant for my next trip back. On our way to every new town, we looked for a chiperia alongside the roads. Chipa was the perfect winter morning snack…so warm and filled with wonderful cheese and dough that melted in your mouth before you even took one bite. There is no denying that I came back from my South American adventure with a few extra wonderful pounds…making my shape a bit more round than I prefer and yet I could not even justify any guilt or regret for having tried such delicious flavors. The list of traditional foods included mbeju, gnocchi, sopa paraquaya, milenesas, lomitos arabe, chorizos, chipa guazu, barbecue meats of all types “a la parilla” and empanadas.

On the first three days of our stay in Paraguay, five of us women drove together cross-country from Asuncion eastbound passing the towns of Caacupe, Coronel Oviedo, and into Ciudad del Este - towards the port of entry into Argentina. It took us five hours in sunshine, rain and fog to arrive at this port where a ferry would then transport us inside our car, floating along the river and arriving fifteen minutes later in Argentina. We almost didn’t make it across the river from Paraguay. Apparently, there was no one ‘official’ available that day to stamp my American passport and allow for departure into the neighboring country. We were stunned, disappointed and upset as you can imagine- having driven five hours to get the point of departure and not being able to get across to the point of entry. After trying to negotiate unsuccessfully for almost 30 minutes, we finally came up with a story about my Argentine boyfriend who was to meet me at the Falls of Iguazu the next morning for the purpose of proposing marriage! Not being able to get to our meeting spot was simply unacceptable; especially after having traveled from the United States for this wonderful chance of finding “true love” on the other side. It was a plot beautifully presented by Marcela’s aunt- which, thankfully, asked us to stay quiet in the car so we didn’t screw up her story! I know for sure, I would not have been able to keep a straight face throughout this negotiation. We did get some sympathy from the ladies that were “patrolling” the border but it wasn’t until we gave one of the workers a $5 US bill that the official stamp somehow made its print upon my passport and we were allowed onto that ferry to cross the river.

The next morning, after a very cold night in a single hotel room housing all five of us together, (where we ran out of hot water within the first hour of checking in and the TV only received strong reception for one station) we made our way to the Iguazu Falls or Cataratas del Iguazu as they call it in South America.

Simply put, there are no words that can describe the immensity of this place. Being there in the early morning, with the foggy dew, and the peaceful train ride through the wilderness towards the Falls, I could only describe the serenity of my spirit as it was being called by thunderous yet melodic sounds of grandeur as the tremendous amount of water (an average of 553 cubic feet per second) plummetted over 269 feet – which can be measured at the Island called Devil’s throat, better known as Gargantua de Diablo. When trying to describe how I felt about the breathtaking view, the only thing I could continue to repeat over and over again in Spanish was “QUE IMPRESIONANTE!” My whole body and spirit felt as if they were out of my physical shell; as if I was looking at this place inside some distant dream…that I was recalling from another life. I could not believe a site like this actually existed in our world. It was a magical experience to say the least; to stand alongside the rails, holding on tightly, closing my eyes, lifting my face toward the early morning sunlight and allowing myself to listen to the rhythm of my own heartbeats pounding in sync with the Falls of Iguazu. Walking away from Gargantua de Diablo, I felt I was being sent back to LIFE again…

Our next stop was truly the whole purpose of our road trip. In the end of our three days, exploring quaint and rustic Paraguay by car, by boat, by foot…I reflected upon how wonderfully spiritual this journey was for me…how in three days, my soul was able to come full-circle. And now I will share and preface my most powerful experience on this journey. For me, it became the most pivotal experience of my first South American adventure. For it to have impact, I must first begin this story by telling you that I was a refugee of war from Laos. We fled Laos during the Vietnam War era and when I was five years old my family was sponsored by a Unitarian Church in Maryland to relocate us from the refugee camp of Thailand to the United States. Secondly, my desires for wanting to travel to Argentina began 2 years ago with a poignant story as to why Posadas, Argentina was such an important stop to make during my journey through South America.

After my father’s passing almost two years ago, I went to visit with our family friend, a Buddhist monk that spiritually cared for my father in his final days. On my visit to our Lao Buddhist temple, located in Catlett, Virginia, Monk Noumay was providing me with spiritual guidance, assisting my mind and heart to understand that life is a cycle and somehow, everything, is interconnected and everyone has a purpose and contributes somehow with their presence and energy in the Universe. He was reminding me that my father is and will always remain a part of my world; that his energy even in the absence of a physical body is with me every day and will remain with me in all my days to come. After finding some solace, we got into a discussion of my passions and my love of world travels. Somehow, we ventured onto the topic of South America. I told him that I had never been there and it was on my list of places to explore. He then mentioned that he was involved a few years ago with a journey to bless a newly built Lao Buddhist Temple in Posadas, Argentina. I was quite surprised by this and asked why in the world would there be a Lao Temple in Argentina? He told me that Argentina, during the Vietnam War era, had opened up their borders as well. Roughly 200 Lao refugee families were accepted into the country relocated to Posadas, Argentina. Eventually, the community of Lao families raised enough funds to build their own temple; creating a place to practice their Buddhists rituals, traditions, and meditations. I was so intrigued by this story. It was on that day with Monk Noumay that I had made a mental note and a spiritual commitment to one day travel to find this community of Lao-Argentines and visit the sacred Temple in Posadas, Argentina.

So there we were…after the magical and surreal experience of the Iguazu Falls, driving another 5 hours- passing farmlands, and taking pictures of every single cow, of every possible size and color you can imagine. The three girls, Marcela, Riciele, and Celeste, were singing “Color Esperanza” while creating seated dance moves as I filmed and re-filmed their choreography. The windows were down, my hair flying around as I fumbled with the digital camera and my mate drink in hand. Laughter and music chased away the minutes…before we knew it, the sun was starting to set and we finally pulled into the sacred grounds of the Lao Buddhist Temple of Posadas.

When I stepped out of the car and planted my feet upon the Earth, there was an energy that traveled up through my legs, my chest, my heart, and through the tear ducts that caused a flow from my eyes. I smiled of excitement, I cried in wonder of how small the world truly is and how beautiful life really is meant to be…if we can only choose to see it more often in such light. The orange glow of the sun crawling slowly for me toward the horizon, allowed me to see this place with my twinkling eyes, to touch the sacred doors of the temple, to take mini breaths and savor the fresh air of Argentina.

The groundkeeper greeted us in perfect Argentine Spanish and when I placed my hands together and bowed my head to greet him with “Sabai dee” – he smiled in acknowledgement and began to speak to me in Laotian. He told me that the head monk was not at the temple, that he had traveled to Cordoba to conduct a special ceremony for a Lao family there. Bizarre as it sounded to know that there were Laotians scattered throughout Argentina…I had to remind myself that it is this way in the United States and all over the world. It simply hit me in that moment, that I could have landed anywhere in the world…and for a brief second…I reflected on the fact that my life’s course could have easily ended on the day that my parent’s escaped with me and my siblings as we crossed the Mekong River into Thailand…my chance to see Paraguay and Argentina as well as the rest of the world is simply a blessing in itself.

So many wonderful things took place on our visit at the temple- too many stories to tell in one sitting but the memories are etched in my mind forever. We eventually made our way from the temple to visit the Lao neighborhood. We stumbled upon two women that were gracious enough to let us into the smaller temple situated in the middle of this community of Lao people. The most amazing part was that the only two women we met were both from the same town in which I was born. How in the world, did the Universe provide such an experience for me! To speak with them in my native language, practice my Spanish, and communicate in understanding that we are all here on this Earth and we all have purpose by simply existing, being, adapting, living…

We were invited inside one of the women’s home to eat traditional Lao bamboo stew and sticky rice. She invited us- without knowing anything about us- to stay the night in her home so she could cook us a real traditional Lao meal in the morning. We were unable to stay because of our tight schedule. However, we were beyond moved by the generosity of her offer. After a brief tour of her home and a garden full of herbs and papaya trees, we exchanged hugs as she and I lingered in our farewell embrace.

When we finally drove away from the neighborhood, I sat in quiet as I could not come up with the words, neither in Spanish, nor English to describe all the emotions running through me. My thoughts were jumbling together, my heart bursting to understand what just took place inside of it. My being…it felt lifted…as if I heard my father’s voice telling me that all things in the Universe are interconnected…that he heard me when I lit the candle inside the temple and prayed for him. He has been with me all along, not only in my dreams, but in these waking moments, every step from the United States, to Paraguay, to the Cataratas de Iguazu, and as I drove away from the Lao temple of Posadas and toward a life where I can now accept and be fully aware that all things are exactly as they should be…

In the next few days that followed, we remained extremely active: visiting the Jesuit Ruins of Encarnacion, going on a shopping spree of souvenirs in Asuncion, touring the Artisan towns outside of the capital city, spending several days visiting with other family members I had come to love and that had grown to love me. I was also grateful to visit certain special people I had considered my Paraguayan family for over 4 years. I built a magical bond with them through photos, through videos and letters, through the Internet messenger and emails. It’s a long story of how they came to be “family” but when I arrived in front of their home in Asuncion, they ran toward me as if I had been born to be loved by them and their biggest hope was simply for me to stay forever. After my one full day and night of visit in their home, every sign of affection they displayed made me believe in true love again!

On the last day in Paraguay, I found myself melancholy while packing my suitcase- trying to fit in all the souvenirs and storing away, in my own head, every beautiful moment we created here. I did not feel quite ready to leave this country. There is still so much left to explore. I felt it was calling me to stay a while longer and yet I believed she was confident in letting me go…as if she knew I would be returning to her one day.

The next morning, after a very cold night in a single hotel room housing all five of us together, (where we ran out of hot water within the first hour of checking in and the TV only received strong reception for one station) we made our way to the Iguazu Falls or Cataratas del Iguazu as they call it in South America.

Simply put, there are no words that can describe the immensity of this place. Being there in the early morning, with the foggy dew, and the peaceful train ride through the wilderness towards the Falls, I could only describe the serenity of my spirit as it was being called by thunderous yet melodic sounds of grandeur as the tremendous amount of water (an average of 553 cubic feet per second) plummetted over 269 feet – which can be measured at the Island called Devil’s throat, better known as Gargantua de Diablo. When trying to describe how I felt about the breathtaking view, the only thing I could continue to repeat over and over again in Spanish was “QUE IMPRESIONANTE!” My whole body and spirit felt as if they were out of my physical shell; as if I was looking at this place inside some distant dream…that I was recalling from another life. I could not believe a site like this actually existed in our world. It was a magical experience to say the least; to stand alongside the rails, holding on tightly, closing my eyes, lifting my face toward the early morning sunlight and allowing myself to listen to the rhythm of my own heartbeats pounding in sync with the Falls of Iguazu. Walking away from Gargantua de Diablo, I felt I was being sent back to LIFE again…

Our next stop was truly the whole purpose of our road trip. In the end of our three days, exploring quaint and rustic Paraguay by car, by boat, by foot…I reflected upon how wonderfully spiritual this journey was for me…how in three days, my soul was able to come full-circle. And now I will share and preface my most powerful experience on this journey. For me, it became the most pivotal experience of my first South American adventure. For it to have impact, I must first begin this story by telling you that I was a refugee of war from Laos. We fled Laos during the Vietnam War era and when I was five years old my family was sponsored by a Unitarian Church in Maryland to relocate us from the refugee camp of Thailand to the United States. Secondly, my desires for wanting to travel to Argentina began 2 years ago with a poignant story as to why Posadas, Argentina was such an important stop to make during my journey through South America.

After my father’s passing almost two years ago, I went to visit with our family friend, a Buddhist monk that spiritually cared for my father in his final days. On my visit to our Lao Buddhist temple, located in Catlett, Virginia, Monk Noumay was providing me with spiritual guidance, assisting my mind and heart to understand that life is a cycle and somehow, everything, is interconnected and everyone has a purpose and contributes somehow with their presence and energy in the Universe. He was reminding me that my father is and will always remain a part of my world; that his energy even in the absence of a physical body is with me every day and will remain with me in all my days to come. After finding some solace, we got into a discussion of my passions and my love of world travels. Somehow, we ventured onto the topic of South America. I told him that I had never been there and it was on my list of places to explore. He then mentioned that he was involved a few years ago with a journey to bless a newly built Lao Buddhist Temple in Posadas, Argentina. I was quite surprised by this and asked why in the world would there be a Lao Temple in Argentina? He told me that Argentina, during the Vietnam War era, had opened up their borders as well. Roughly 200 Lao refugee families were accepted into the country relocated to Posadas, Argentina. Eventually, the community of Lao families raised enough funds to build their own temple; creating a place to practice their Buddhists rituals, traditions, and meditations. I was so intrigued by this story. It was on that day with Monk Noumay that I had made a mental note and a spiritual commitment to one day travel to find this community of Lao-Argentines and visit the sacred Temple in Posadas, Argentina.

So there we were…after the magical and surreal experience of the Iguazu Falls, driving another 5 hours- passing farmlands, and taking pictures of every single cow, of every possible size and color you can imagine. The three girls, Marcela, Riciele, and Celeste, were singing “Color Esperanza” while creating seated dance moves as I filmed and re-filmed their choreography. The windows were down, my hair flying around as I fumbled with the digital camera and my mate drink in hand. Laughter and music chased away the minutes…before we knew it, the sun was starting to set and we finally pulled into the sacred grounds of the Lao Buddhist Temple of Posadas.

When I stepped out of the car and planted my feet upon the Earth, there was an energy that traveled up through my legs, my chest, my heart, and through the tear ducts that caused a flow from my eyes. I smiled of excitement, I cried in wonder of how small the world truly is and how beautiful life really is meant to be…if we can only choose to see it more often in such light. The orange glow of the sun crawling slowly for me toward the horizon, allowed me to see this place with my twinkling eyes, to touch the sacred doors of the temple, to take mini breaths and savor the fresh air of Argentina.

The groundkeeper greeted us in perfect Argentine Spanish and when I placed my hands together and bowed my head to greet him with “Sabai dee” – he smiled in acknowledgement and began to speak to me in Laotian. He told me that the head monk was not at the temple, that he had traveled to Cordoba to conduct a special ceremony for a Lao family there. Bizarre as it sounded to know that there were Laotians scattered throughout Argentina…I had to remind myself that it is this way in the United States and all over the world. It simply hit me in that moment, that I could have landed anywhere in the world…and for a brief second…I reflected on the fact that my life’s course could have easily ended on the day that my parent’s escaped with me and my siblings as we crossed the Mekong River into Thailand…my chance to see Paraguay and Argentina as well as the rest of the world is simply a blessing in itself.

So many wonderful things took place on our visit at the temple- too many stories to tell in one sitting but the memories are etched in my mind forever. We eventually made our way from the temple to visit the Lao neighborhood. We stumbled upon two women that were gracious enough to let us into the smaller temple situated in the middle of this community of Lao people. The most amazing part was that the only two women we met were both from the same town in which I was born. How in the world, did the Universe provide such an experience for me! To speak with them in my native language, practice my Spanish, and communicate in understanding that we are all here on this Earth and we all have purpose by simply existing, being, adapting, living…

We were invited inside one of the women’s home to eat traditional Lao bamboo stew and sticky rice. She invited us- without knowing anything about us- to stay the night in her home so she could cook us a real traditional Lao meal in the morning. We were unable to stay because of our tight schedule. However, we were beyond moved by the generosity of her offer. After a brief tour of her home and a garden full of herbs and papaya trees, we exchanged hugs as she and I lingered in our farewell embrace.

When we finally drove away from the neighborhood, I sat in quiet as I could not come up with the words, neither in Spanish, nor English to describe all the emotions running through me. My thoughts were jumbling together, my heart bursting to understand what just took place inside of it. My being…it felt lifted…as if I heard my father’s voice telling me that all things in the Universe are interconnected…that he heard me when I lit the candle inside the temple and prayed for him. He has been with me all along, not only in my dreams, but in these waking moments, every step from the United States, to Paraguay, to the Cataratas de Iguazu, and as I drove away from the Lao temple of Posadas and toward a life where I can now accept and be fully aware that all things are exactly as they should be…

In the next few days that followed, we remained extremely active: visiting the Jesuit Ruins of Encarnacion, going on a shopping spree of souvenirs in Asuncion, touring the Artisan towns outside of the capital city, spending several days visiting with other family members I had come to love and that had grown to love me. I was also grateful to visit certain special people I had considered my Paraguayan family for over 4 years. I built a magical bond with them through photos, through videos and letters, through the Internet messenger and emails. It’s a long story of how they came to be “family” but when I arrived in front of their home in Asuncion, they ran toward me as if I had been born to be loved by them and their biggest hope was simply for me to stay forever. After my one full day and night of visit in their home, every sign of affection they displayed made me believe in true love again!

On the last day in Paraguay, I found myself melancholy while packing my suitcase- trying to fit in all the souvenirs and storing away, in my own head, every beautiful moment we created here. I did not feel quite ready to leave this country. There is still so much left to explore. I felt it was calling me to stay a while longer and yet I believed she was confident in letting me go…as if she knew I would be returning to her one day.